TLDR: This blog will discuss:

1 - A very simple VAE introduction

2 - Several papers that use VAE architecture for various symbolic music modelling tasks

3 - General thoughts on several aspects of VAE in symbolic music modelling

1 - VAE

We know about the VAE’s ELBO function as below (refer here for ELBO derivation):

$$E_{z\sim q(Z|X)}[\log p(X|Z)] - \beta \cdot \mathcal{D}_{KL}(q(Z|X) || p(Z))$$

The first term represents reconstruction accuracy, as the expectation of reconstructing \(X\) given \(Z\) needs to be maximized. Latent code \(z\) is sampled from a learnt posterior \(q(Z|X)\).

The second term represents KL divergence – how deviated is the learnt posterior \(q(Z|X)\) from the prior \(p(Z)\). According to BetaVAE paper, the \(\beta\) term weights the influence of KL divergence in the ELBO function.

The prior distribution \(p(Z)\), in simple terms, is the assumption of how your data points are distributed. A common choice of prior distribution is the standard Gaussian \(\mathcal{N}(0, \mathcal{I})\). However, many start to think that a more natural choice of distribution should be a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) – $$\sum_{i=1}^{K} \phi_{i} \cdot \mathcal{N}(\mu_{i}, \Sigma_{i})$$ as the distribution of the data points could be mixtures of Gaussian components, rather than just one single standard Gaussian.

The posterior distribution \(q(Z|X)\), in simple terms, is the “improvement” that you make on your assumed distribution of \(Z\), after inspecting data samples \(X\). Since the true posterior \(p(Z|X)\) is intractable, hence we use variational inference to get an approximation \(q(Z|X)\), and made it learnt by a neural network.

The ultimate intuition of the VAE framework is to encode the huge data space into a compact latent space, where meaningful attributes can be extracted and controlled relatively easier in lower dimension. Hence, the objective would be: how can we utilize the latent space learnt for a multitude of music application tasks, including generation, interpolation, disentanglement, style transfer, etc.?

2 - Application

Symbolic music domain refers to the usage of high-level symbols such as event tokens, text, or piano roll matrices as representation during music modelling. Audio-based music modelling is not covered in this scope. The reason of using symbolic music representation for modelling is that it incorporates higher level features such as structure, harmony, rhythm etc. directly within the representation itself, without the need of further preprocessing.

To study the objective above, below we list and discuss several papers that apply VAE framework on symbolic music modelling –

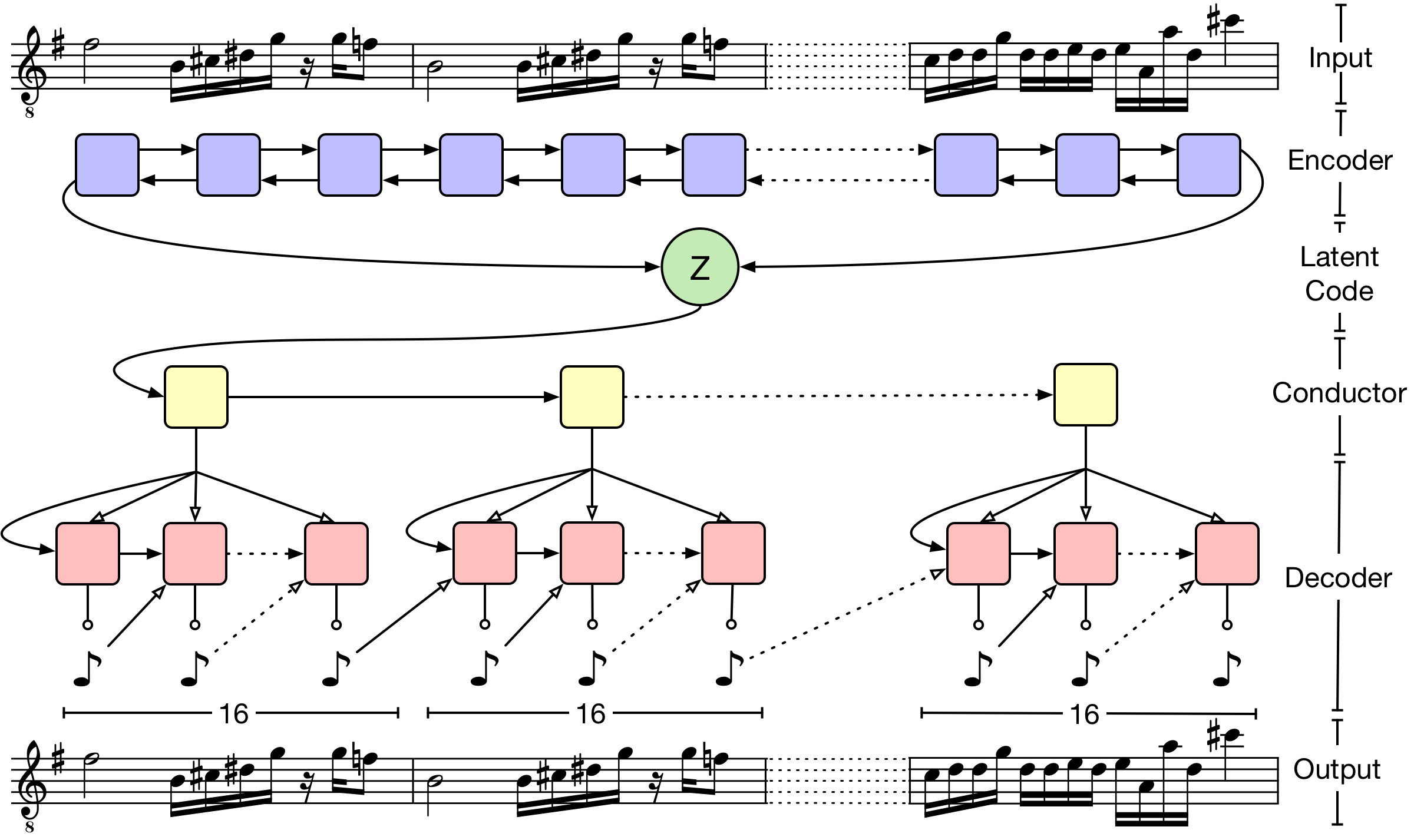

1 - MusicVAE

Published at: ICML 2018

Dataset type: Single track, monophonic piano music

Representation used: Piano roll (final layer as softmax)

Novelty: This should be one of the very first widely known papers that used VAE on music modelling, bringing in the idea from Bowman et al. The key contributions include:

- it clearly demonstrates the power of condensing useful musical information in the latent space. Variations in generated samples are more evident in latent space traversal, instead of data space.

- the “conductor” layer responsible for measure-level embeddings helps in preserving long term structure and reconstruction accuracy in longer sequences.

An extension of this work on multi-track music is available here.

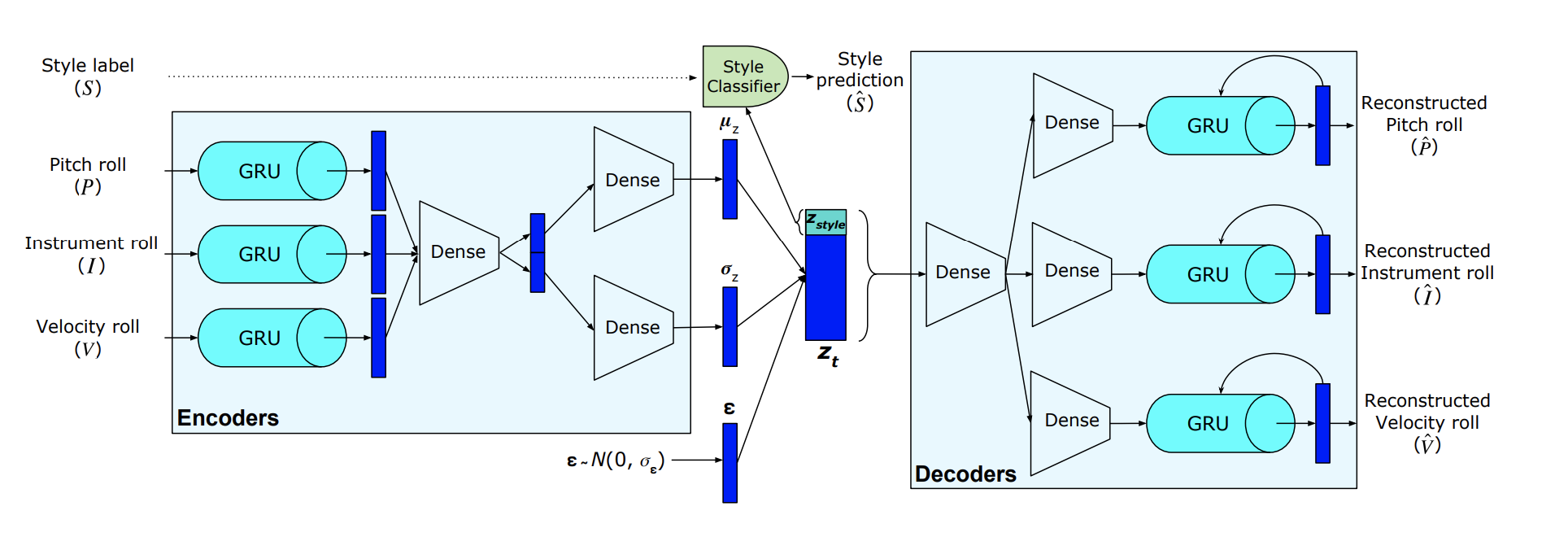

2 - MIDI-VAE

Published at: ISMIR 2018

Dataset type: Multi-track, polyphonic music across jazz, classical, pop

Representation used: Piano roll for each track. Note: for each timestep, instead of modelling 1 n-hot vector, n 1-hot vectors are modelled (final layer as softmax)

Novelty: One of the very first music style transfer papers in the symbolic domain.

- The idea is to disentangle a portion out of the latent vector to be responsible for style classification, while the remaining should encode the characteristics of the data sample. During generation, \(z_{S_{1}}\) will be swapped to \(z_{S_{2}}\), and decoded with the remaining part of the latent vector.

- They also proposed a novel method to represent multi-track polyphonic music by training 3 GRUs, each responsible for pitch, instrument and velocity, used in both encoder and decoder part.

How could we get both \(z_{S_{1}}\) and \(z_{S_{2}}\) for style-swap is not detailed in the paper. We assume that we need pairing data samples of style \(S_{1}\) and \(S_{2}\) each, encode them into latent vectors, cross-swap the style latent part and the residual latent part, and then decode.

However in this framework, \(z_{S}\) is constrained to encode style-related information, but not necessarily to exclude sample-related information – sample-related information could also exist in \(z_{S}\). Ensuring identity transformation after cross-swapping style and sample latent codes may be a challenge in this framework, however ideas of using adversarial training to ensure sample invariance, such as in Fader Networks paper or in this timbre disentanglement paper should be easily extended from here.

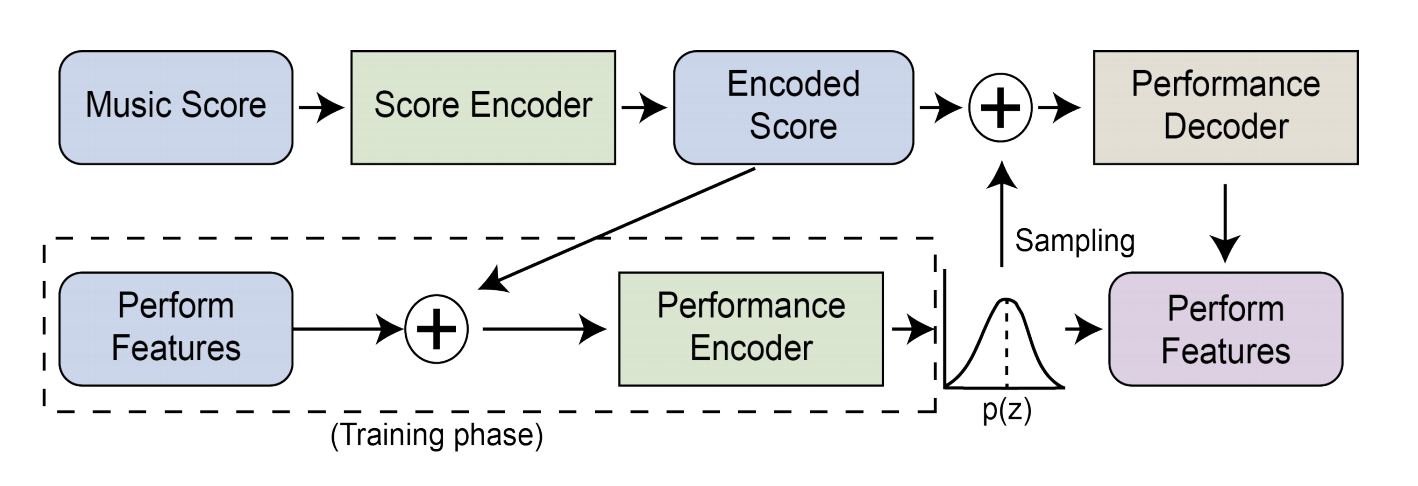

3 - VirtuosoNet

Published at: ISMIR 2019

Dataset type: Classical piano music

Representation used: Score and performance features (refer to this paper)

Novelty: This paper focuses on expressive piano performance modelling. The key contributions are:

- As they argue that music scores can be interpreted and performed in various styles, this work uses a conditional VAE (CVAE) architecture for the performance encoder and decoder. The additional condition fed in is the score representation learnt by a separate score encoder.

- The score encoder consists of 3 levels, each encoding note, beat and measure information respectively. This work also uses the idea of hierachical attention, such that information is being attended on different levels: note, beat and measure during encoding

- During generation, it either randomly samples the style vector \(z\) from a normal distribution prior, or uses a pre-encoded \(z\) from other performances to decode performance features.

- An extension of this work, GNN for Piano Performance Modelling, incorporates the idea of using graphs to model performance events.

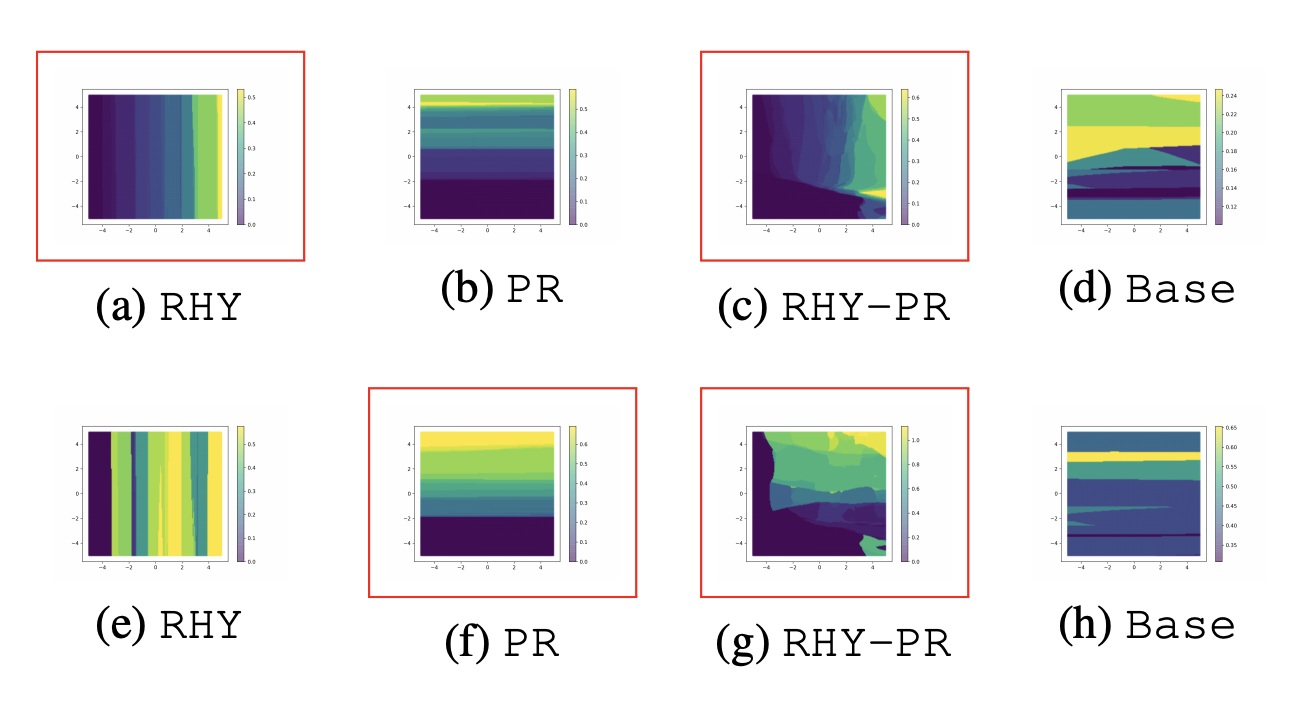

4 - Latent Space Regularization for Explicit Control of Musical Attributes

Published at: ML4MD @ ICML 2019

Dataset type: Single track, monophonic music

Representation used: Piano roll (final layer as softmax)

Novelty: This two-page extended abstract tackles the problem of controllable music generation over desired musical attributes. The simple yet powerful idea is that we can regularize some dimensions within the encoded latent vector to reflect the changes in our desired musical attributes (such as rhythm density, pitch range, etc.).

The author suggests to add a regularization loss term during training, in the form of

$$ MSE(tanh(\mathcal{D}_{z_r}), sign(\mathcal{D}_a))$$

where \(\mathcal{D}\) represents distance matrix, which is a 2-dimensional square matrix of shape \((|S|, |S|)\), containing the distances (taken pairwise) between the elements of a set \(S\).

\(\mathcal{D}\) is the distance matrix of the \(r^{th}\) dimension value of encoded \(z\) for each sample, while \(\mathcal{D}_{a}\) is the distance matrix of musical attributes for each sample. The idea is to incorporate the relative distance of musical attributes within a training batch by regularizing the \(r^{th}\) dimension of \(z\), such that \(z^i_r < z^j_r \Longleftrightarrow a^i < a^j\).

The interesting ideas that I find in this work is that the regularization loss captures relative distance instead of absolute distance, i.e. using \(MSE(\mathcal{D}_{z_r}, \mathcal{D}_a)\), or even more directly, using \(MSE(z_r, a)\). According to the author, this is to prevent the latent space to be distributed according to the distribution of the attribute space, as \(z_r\) is learnt to get closer to \(a\). This might be in direct conflict with the KL-divergence loss since this is trying to enforce a more Gaussian-like structure to the latent space. Hence, there might exists a tradeoff here between (1) the precision of \(z_r\) modelling the actual attribute values (as using relative distance will not be that precise as using absolute values), and (2) the correlation metric between \(z_r\) and \(a\).

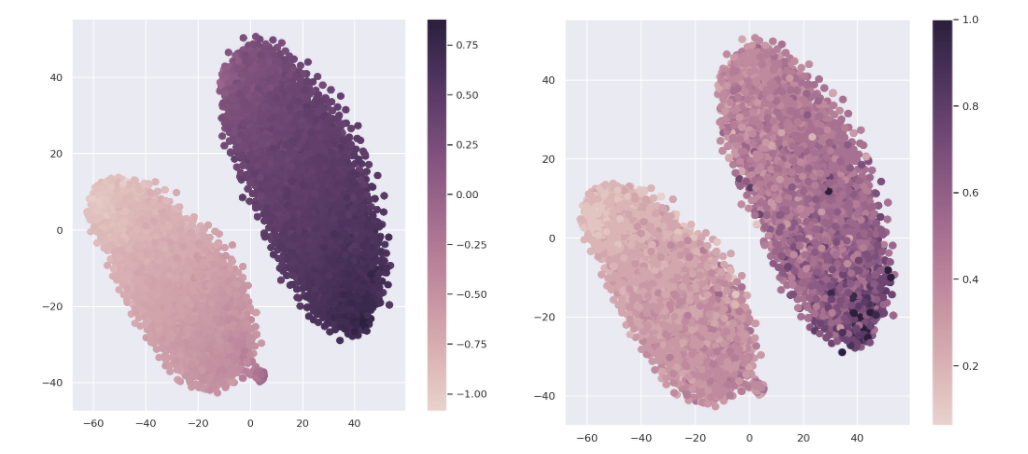

Figure below (through my own experiment) shows the same t-SNE diagram, the left side colored using regularized \(z_r\) values, and the right side colored using actual \(a\) values. We can see that the overall trend of value change is indeed captured, but the precision between values of \(z_r\) and \(a\) on individual samples are not necessarily accurate.

5 - Deep Music Analogy via Latent Representation Disentanglement

Published at: ISMIR 2019

Dataset type: Single track, monophonic piano music

Representation used: Piano roll (final layer as softmax)

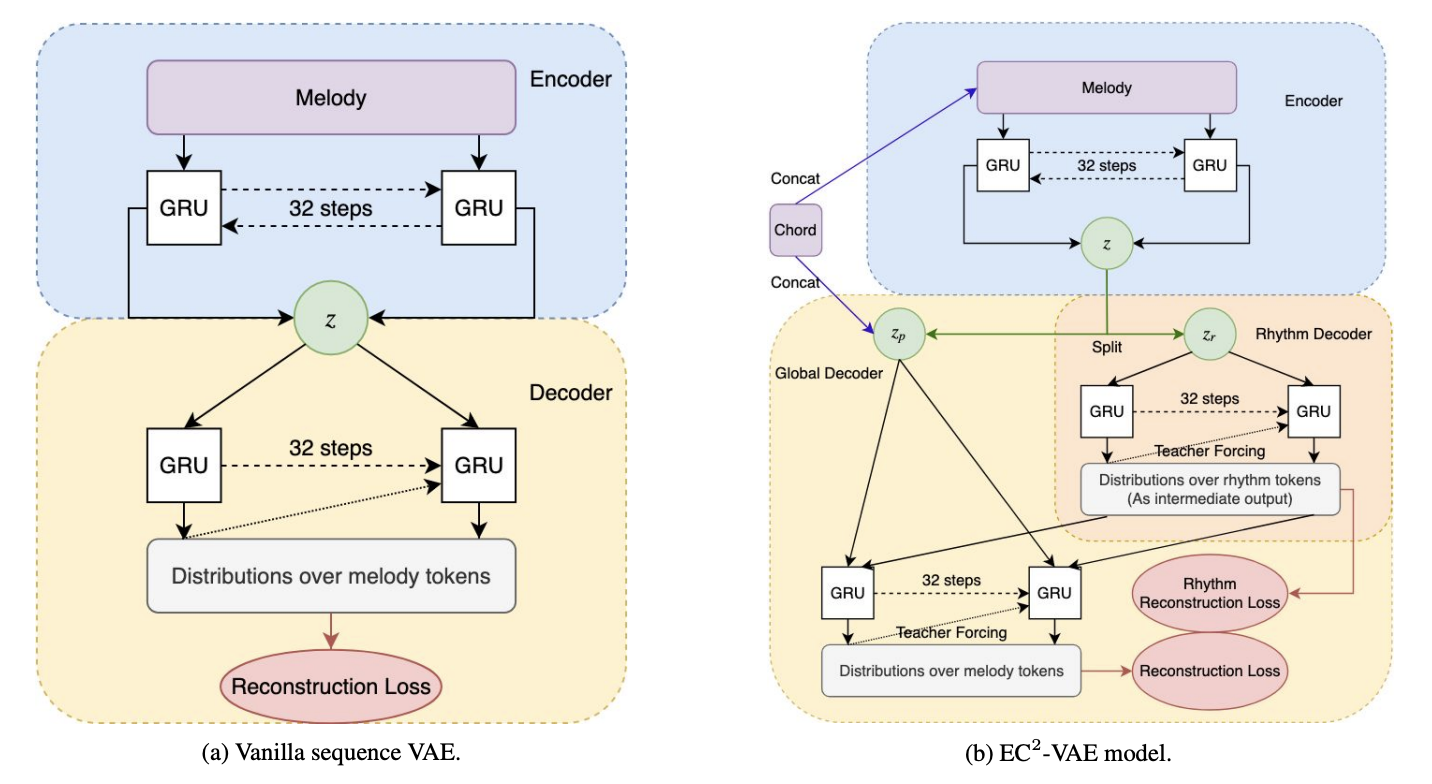

Novelty: “Deep music analogy” shares a very similar concept with music style transfer. This work focuses on disentangling rhythm and pitch from monophonic music, hence achieving controllable synthesis based on a given template of rhythm, a given set of pitches, or a given chord condition.

- The proposed EC2-VAE architecture splits latent \(z\) into 2 parts – \(z_{p}\) and \(z_{r}\), where \(z_{r}\) is co-erced to reconstruct rhythmic patterns of the sample. Both \(z_{p}\) and \(z_{r}\), together with the chord condition, is used to decode into the original sample.

- Another point of view is to see it as a type of latent regularization – part of the latent code is “regularized” to be controllable on a particular type of attribute, which in this work the regularization is done by adding a classification loss output by a rhythm classifier.

- Objective evaluation is of 2-fold:

- After pitch transposition, \(\Delta z_{r}\) should not be changed much and instead \(\Delta z_{p}\) should be changing. This is by measuring the L1-norm of change in \(z\).

- Modifying evaluation methods from FactorVAE, this work proposes to evaluate disentanglement by measuring average variances of the values in each latent dimension after pitch / rhythm augmentation in input samples. Should the disentanglement be successful, when rhythm augmentation is done, the largest variance dimensions should correspond to the dimensions that are explicitly conditioned to model rhythm attributes (and vice versa for pitch attribute).

6 - Controlling Symbolic Music Generation Based On Concept Learning From Domain Knowledge

Published at: ISMIR 2019

Dataset type: Single track, monophonic piano music

Representation used: Piano roll (final layer as softmax)

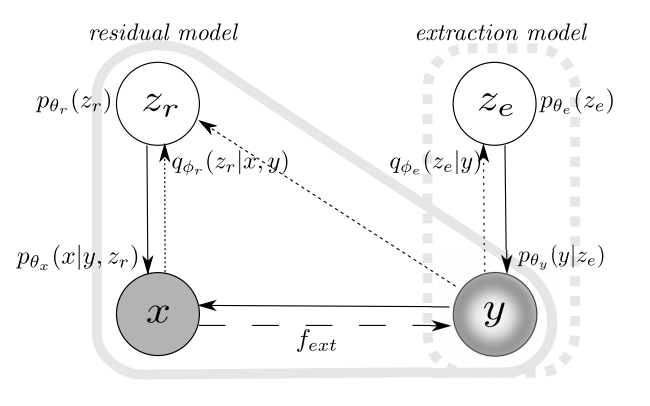

Novelty: This work proposes a model known as ExtRes, which stands for extraction model and residual model. The residual model part is a generative model, while the extraction model allows learning reusable representation for a user-specified concept, given a function based on domain knowledge on the concept.

From the graphical model, we can see that:

- During inference, latent code \(z_e\) is learnt to model user-defined attributes \(y\) via a probabilistic encoder with posterior \(q_{\phi_{e}}(z_e|y)\) and parameters \(\phi_{e}\) (the parameters are, in this case, the neural network weights). Separately, latent code \(z_r\) is learnt to model input sample \(x\) via another probabilistic encoder with posterior \(q_{\phi_{r}}(z_r|x, y)\) and parameters \(\phi_{r}\), taking in \(y\) as an additional condition during encoding.

- During generation, latent code \(z_e\) and \(z_r\) and both sampled from a standard Gaussian prior. A decoder with parameters \(\theta_y\) is trained to decode \(z_e\) into \(y\), and a separate decoder with parameters \(\theta_x\) is trained to decode \(z_r\) into \(x\), with an additional condition of \(y\).

The final loss function is hence consists of 4 terms:

- the reconstruction loss of the input sample \(x\);

- the reconstruction loss of the attribute sequence \(y\);

- the KL divergence between posterior \(q_{\phi_{e}}(z_e|y)\) and prior \(p(z_e)\) for extraction model;

- the KL divergence between posterior \(q_{\phi_{r}}(z_r|x, y)\) and prior \(p(z_r)\) for residual model.

Here, we can see that the residual model is trained in a CVAE manner, such as to achieve conditional generation, with condition \(y\) should \(y\) be either obtained from (1) the learnt extraction model, or (2) the dataset itsef (in this case, it resembles with the teacher-forcing training technique).

Other relevant papers that we would like to list here include:

7 - A Classifying Variational Autoencoder with Application to Polyphonic Music Generation

8 - MahlerNet: Unbounded Orchestral Music with Neural Networks

9 - Latent Constraints: Learning to Generate Conditionally from Unconditional Generative Models

10 - GLSR-VAE: Geodesic Latent Space Regularization for Variational AutoEncoder Architectures

3 - Thoughts and Discussion

I hereby list some of my thoughts regarding these works as above for future discussion and hopefully for even more exciting future work.

1 - Common usage of the latent code

We could observe that a whole lot of applications of VAE are focusing on music attribute / feature modelling. This is more commonly seen as it spans over several types of tasks including controllable music generation, higher level style transfer, and lower level attribute / feature transfer. Normally, a latent space is being encoded for each factor, so as to achieve separation in modelling different factors in the music piece. During generation, a latent code that exhibit the desired factor is either (i) encoded via the learnt posterior from an existing sample, or (2) sampled through a prior from each space, and then being combined and decoded.

Here, we can summarize some key aspects that one would encounter while using VAE for music attribute modelling:

(i) disentanglement: how are the attributes being disentangled from each other, so as to ensure that each latent space governs one and only desired factor;

(ii) regularization: how is the latent space being regularized to exhibit a certain desired factor – either by adding in a classifier, or using some self-defined regularization loss.

(iii) identity preservation: how can we ensure that the identity of the sample can be retained after transformation, while only being changed on the desired factor? Here, we argue that it is determined by 2 factors: the reconstruction quality, and the disentanglement quality of the model. For ensuring disentanglement quality, a common strategy is to use adversarial training, such that to ensure the latent space be invariant on the non-governing factors.

2 - On \(\beta\) value

It is an interesting observation to note that commonly within the literature of VAE music modelling, a lot of the work uses a relatively low \(\beta\) value. Among the first 5 papers discussed above, each of them uses \(\beta\) value of 0.2, 0.1, 0.02, 0.001, and 0.1 respectively, commonly accompanied by an annealing strategy. Only for the 6th paper, \(\beta\) value is within a range of [0.7, 1.0] depending on the attribute modelled.

It seems that although we are mostly modelling only monophonic or single-track polyphonic music, it has been hard enough to retain the reconstruction accuracy on a higher \(\beta\) value. Additionally, the MIDI-VAE paper has further showed that the reconstruction accuracy are very much poorer given higher \(\beta\) values. It would be interesting to unveil the reasons behind why sequential music data are inherently hard to achieve higher reconstruction accuracy. More important, given the fact of the tradeoff between disentanglement and reconstruction as proposed by \(\beta\)-VAE, how could we find a balanced sweet spot for good disentanglement provided with such low range of \(\beta\) values remain an interesting challenge.

3 - On music representation used

Common music representation used during modelling include MIDI-like events, piano roll or text (for more details refer to this survey paper). For VAE in music modelling, the most common used representation is either MIDI-like events (mostly for polyphonic music), or piano roll. Hence, the encoder and decoder used in VAE are often autoregressive, either using LSTMs, GRUs, or even Transformers. Often times, the encoder or the decoder part can be further split into hierachies, with each level modelling low to high-level features from note, measure, phrase to the whole segment.

Recently, Jeong et al. proposed to use graphs instead of normal sequential tokens to represent music performances. Although the superiority of using graph as compared to common sequential representations is not evident yet, this might be a promising and interesting path to pursue for future work.

4 - On the measure of “controllability”

How could we evaluate if a model has a “higher controllability”, on a given factor, during generation? The most related one might be by Pati et al., whom has given an interpretability metric which mainly returns a score depicting the correlation between the latent code and the attribute modelled.

5 - Can VAE be an end-to-end architecture for music generation?

From most of the works above, we see VAE being used to generate mainly short segments of music (4 bars, 16 beats, etc.), which are unlike language modelling approaches such as Music Transformer, MuseNet, and Pop Music Transformer that can generate minute-long decent music pieces with observable long term structure.

Latent space models and language models might each have their own strengths in the context of music generation. Latent space models are useful for feature / attribute modelling, with an extension of usage on style transfer; whereas language models are strong at generation long sequences which exhibit structure. Combining the strengths of both approaches might be an interesting direction for improving the quality and flexibility of state-of-the-art music generation models.