TLDR: This blog will discuss:

1 - A very brief survey on recent cover song detection systems

2 - Challenges in deploying cover song detection systems to production

1 - Introduction

Recently, I had the opportunity to experiment, build and deploy cover detection systems (CSD) to production. I would love to take this chance to note down some observations and thoughts throughout building the system, and summarize some issues that I find while deploying such systems to production.

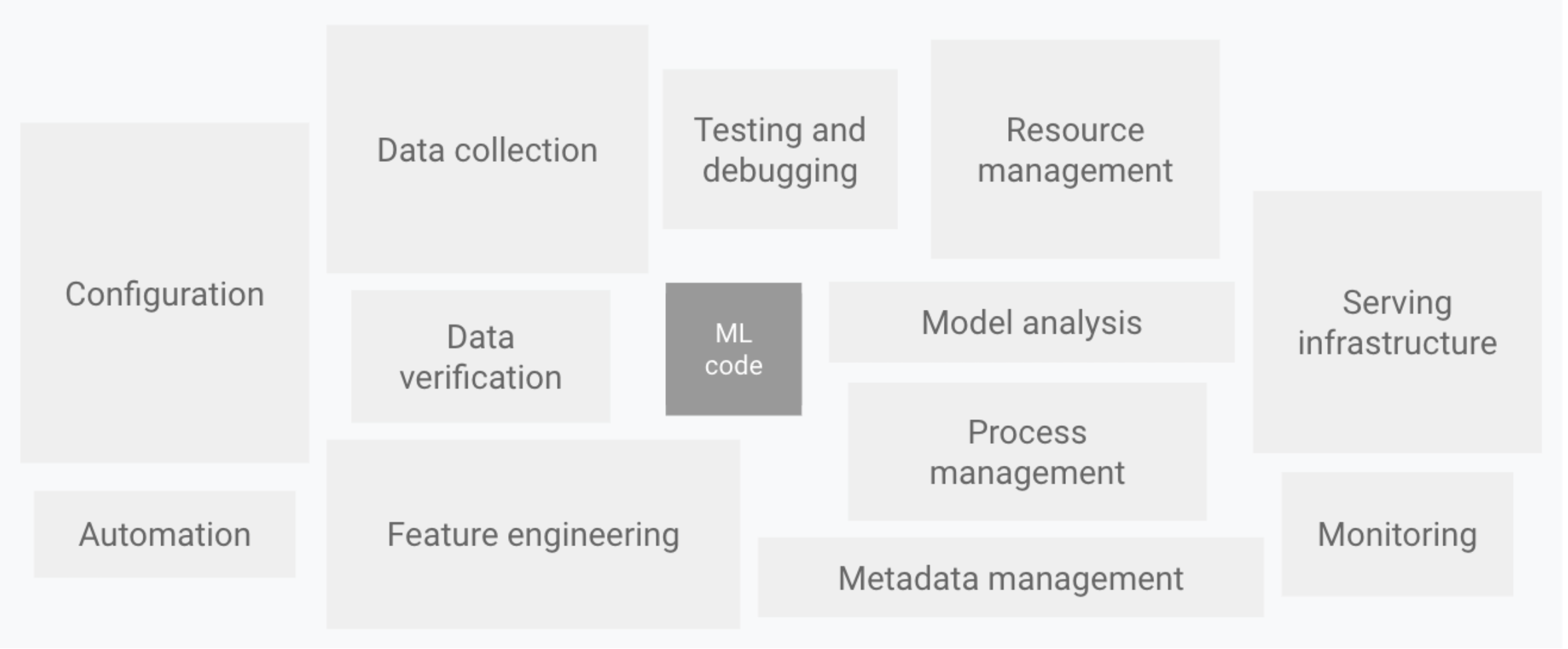

The experience of bringing academia work into production is a mixture of exciting and demoralizing moments. The exciting part is that you are really creating value for the users / stakeholders with your meticulously-trained, carefully-assessed “baby” - your model. Sometimes, it might even be the case that the faster the inference speed of your model / system, the more revenue is generated. The demoralizing part is that there is a very, very, very long way from bringing academia models to serving production use cases. A model with 95% accuracy on benchmarks would not suffice, it also has to be fast enough, cost-effective, has minimal downtime, best not to drain too much GPU money, and most importantly robust enough to serve any use cases provided by (often more than one type of) clients. 95% of the problems are often very boring problems, but they are necessary to make the 5% interesting part shine.

I could now understand clearly why the model is often not the primary concern within the stack, especially when the team is resource limited. More resources can be directed to R&D afterwards, but a seamlessly served model, though mediocre in performance, with minimal downtime and latency, is of priority to showcase the potential of the proposed technology and drive momentum.

2 - A Very Brief Survey on Recent Advances in Cover Song Detection

Cover song detection, to the music industry, is the potential “upgraded” version of audio fingerprinting systems, because audio fingerprinting systems can only identify originals, but it cannot withstand variance in instrumentation / arrangement. Whereas for CSD, if we can already identify a cover track, then identifying the original track is basically a trivial problem. This is why CSD systems are of high interests in e.g. the music rights / licensing / publishing bodies, to identify “music of any version, in any performance / cover, in any form”.

To the very best of my knowledge, I roughly categorized the common types of CSD algorithms into the following 4 categories: dominant melody based, harmonic based, hybrid methods, and end-to-end based.

Dominant Melody-Based

The idea is to match the dominant melody of the same composition, because cover tracks share similar dominant melody patterns, although it might be transposed to a different pitch. The most recent work is by Doras et al. 2019 and Doras et al. 2020, which trains a network to learn dominant melody embeddings that reflect melody similarity via variants of triplet-loss functions. Several works in this category include Sailer et al. and Tsai et al., which commonly extract the dominant melody, calculate the pitch intervals (for pitch invariance) and run alignment algorithms such as dynamic time warping or Smith-Waterman algorithm to retrieve a similarity score.

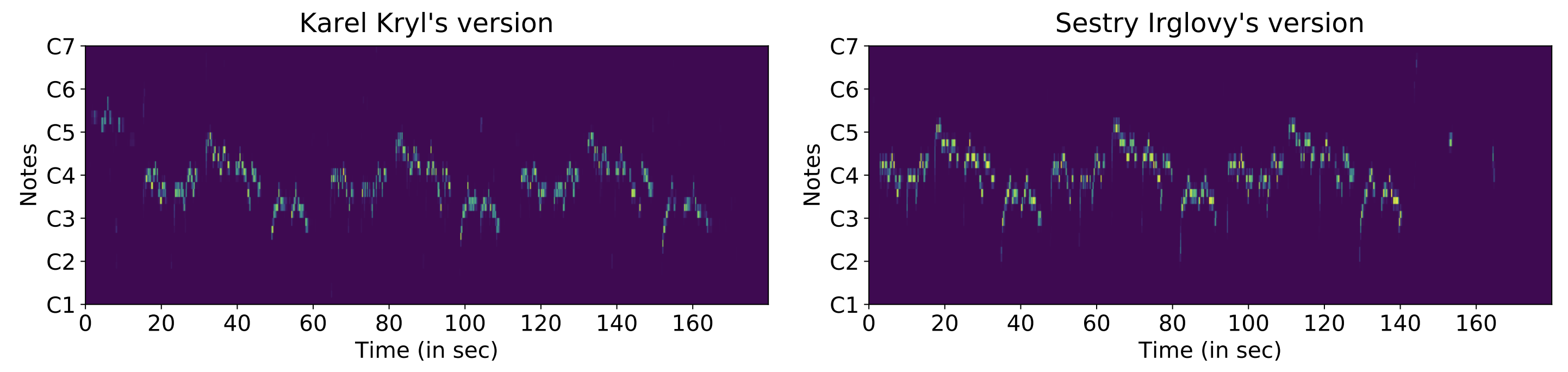

Dominant melodies extracted for original and cover track.

However, the performance of dominant melody based solutions is tightly coupled with the accuracy of the extracted dominant melody (see this recent work on F0 estimation). Dominant melody extraction might be disrupted by (i) mistaking accompaniment as melody, or vice versa, and (ii) “wobbly” pitch glides due to singing techniques. For alignment-based methods, since we often need pitch intervals to calculate cover similarity, it is highly sensitive to the unwanted notes introduced in the melody extraction phase. Dominant melody methods could also have missed out songs with (i) raps (no-pitch content), and also (ii) instrumentals because models are often built catering towards vocal tracks. If the melody extraction module is a trained neural network, it could also be biased on e.g. the genre, vocal presence, vocal gender of tracks it is trained on, hence lack generalization.

Harmonic-Based

The idea is to use tonal features, e.g. chromas (or pitch class profiles) or chords, as covers share similar tonal progression. The most recent work is by MOVE and Re-MOVE which uses cremaPCP as the feature representation, training (musically motivated) neural networks to learn similarity via triplet-loss functions. For a long time, Serra et al.‘s method using HPCP as representation, calculating cross recurrence plots and calculating similarity scores using the QMax algorithm has been the state-of-the-art method in CSD.

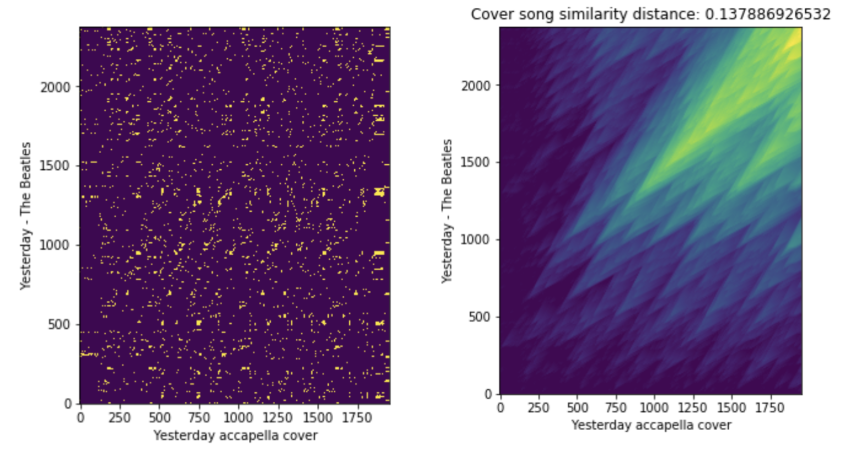

HPCP cross recurrence plot and cover similarity via QMax algorithm.

The potential problem in harmonic-based methods is that there can be more false positives in a larger corpus, because there exists more tracks with similar harmonic progressions / pitch class profiles (especially in the pop genre) when compared to a reference track. For non-neural-network methods, algorithms aligning 2D cross recurrence plots between query and reference are in quadratic time, which imposes a limit on detection speed and hence harder to scale.

Hybrid Methods

The most recent hybrid attempt is by Yesiler and Doras which combines both dominant melody and cremaPCP as representations. The paper illustrates that both features are complementary and a simple averaging in scores could boost the performance. Some other hybrid methods include MFCC and HPCP fusion, with improvements using ensemble-based comparison.

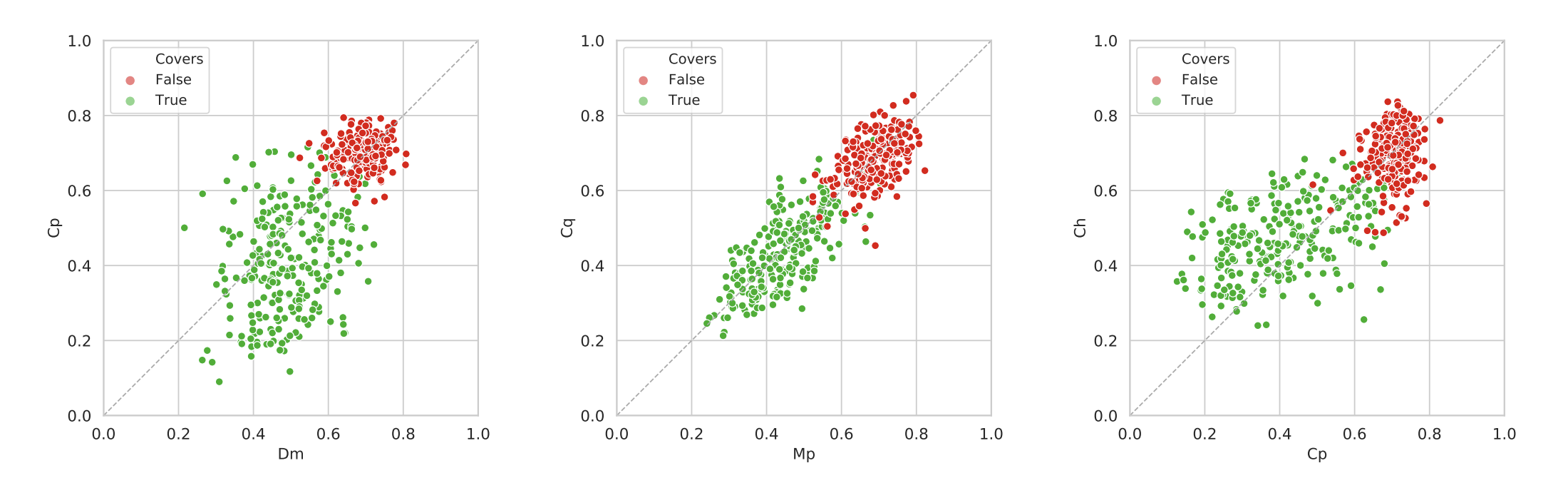

Normalized distance plot for: dominant melody VS cremaPCP (left), multi-pitch VS CQT (mid), and cremaPCP VS Chroma (right). Each feature reflects a different aspect of similarity, hence suggesting complementarity via feature combination.

From a system standpoint, hybrid methods add levels of complexity when building the CSD system. Parallelizing the extraction of multiple input features and the respective processing steps could be more complex depending on the pipeline, and it would require more resources to maintain the more components involved and the higher level of complexity.

There is also an important work which introduces the representation of 2D Fourier Transform (2DFT) for CSD by Seetharaman et al.. 2DFT (see this video for explanation) breaks down images into sums of sinusoidal grids at different periods and orientations, represented by points in the 2DFT. Running 2DFT on CQT spectrogram gives a key-invariant representation of the audio. The model achieved good results on “faithful covers”, but failed when the cover has a larger extent of variation.

End-to-End Based

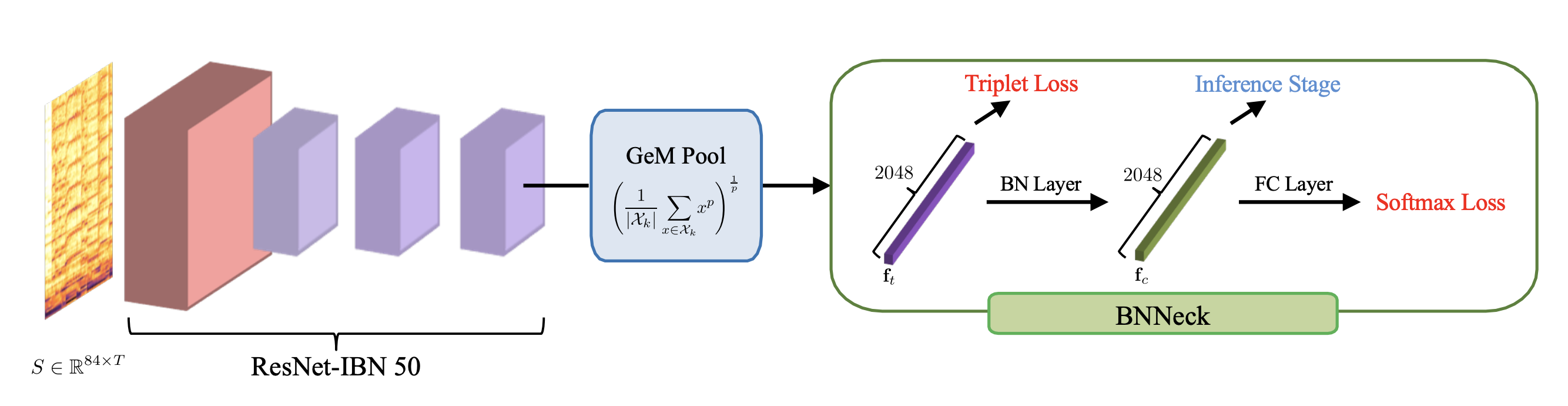

End-to-end based systems are often favoured due to its simplicity for building, as you only need a single component instead of multiple components to make the system work. A series of work by Yu et al. including CQTNet, TPPNet, and the recent ByteCover lies in this domain. The idea is to use just CQT spectrograms as input representations, and train carefully designed neural networks to directly output the similarity score between two songs. ByteCover even referenced CSD as a person re-identification problem, and its architecture design is largely adapted from re-ID, while achieving state-of-the-art performance by far.

ByteCover architecture.

3 - Thoughts and Discussion regarding CSD in Production

I would love to discuss the four issues below that I have encountered while building CSD systems in production, which shows some different concerns between production and research.

Snippet Detection

Because CSD is a potential upgrade for audio fingerprinting systems, it is pretty much hoped to perform like e.g. Shazam / Soundhound, which can detect a track within only few seconds of recording. Acoustic fingerprinting is very good in this scenario because you can already find confident matches of fingerprint hashes with only seconds of recording.

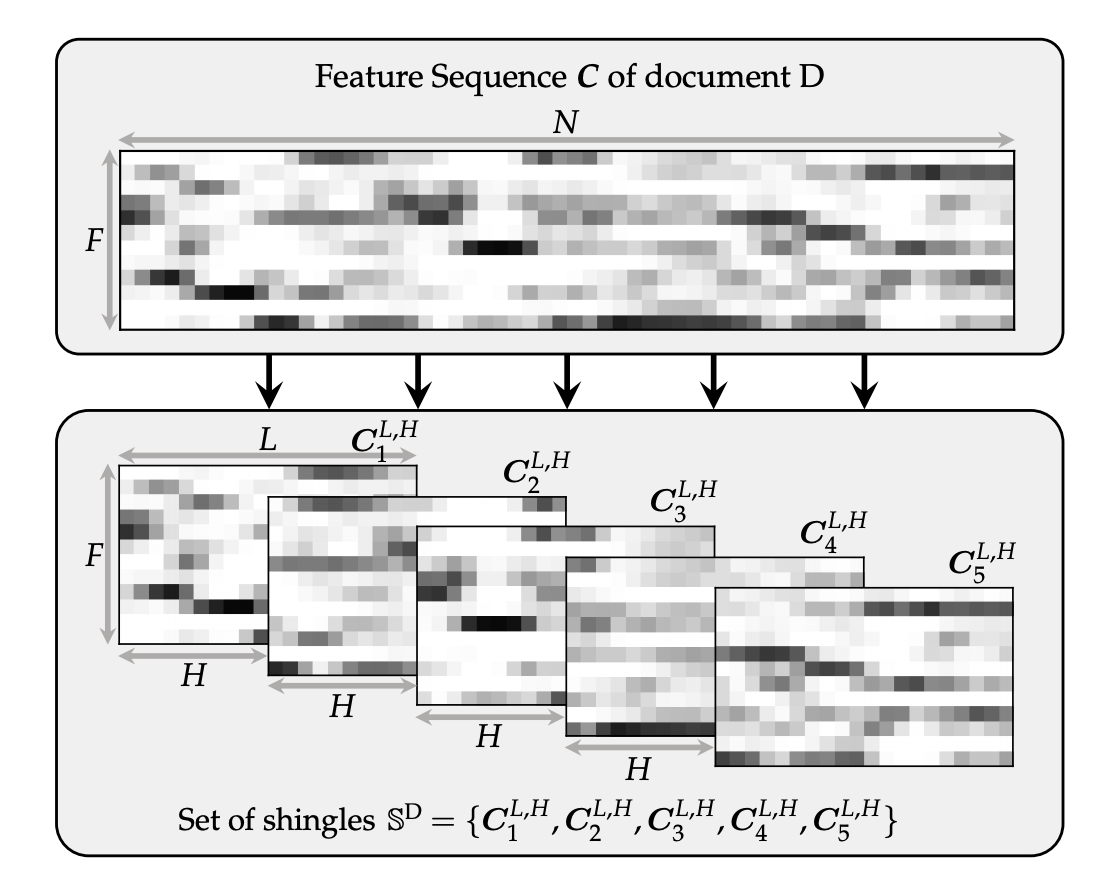

But, detecting a cover song from just snippets is totally different - there can be cases where the seconds exhibit in the query (i) doesn’t show resemblance / marginally resembles with the reference (irrelevant sections chosen); or more often (ii) resembles more with other references depending on the feature used (e.g. similar melody / tonal progression). Currently, most models don’t generalize well to snippet forms of query - alignment based methods are dependent on query & reference lengths, and deep-learning based methods are trained on corpuses of full tracks. Most CSD research also do not tackle this aspect of the problem - the closest I could find would be by Zalkow et al. which works on “shingles” in classical music.

Research work also did not focus on which section (where) in the reference has the highest resemblance with the query (or vice versa). This is extremely useful for identifying e.g. long remixes / performances with more than one work involved. Alignment-based methods like DTW & Smith Waterman are natural for answering this question, but it might be non-trivial for deep metric-learning based methods.

Benchmark Results May Not Transfer To Other Datasets

The performance of CSD algorithms are highly dependent on what kind of corpus you are comparing against. I find it possible to have a model performing very well on large, well-known benchmark datasets, but it could still perform badly on another small, curated test set, simply because there are too many “competitive candidates” for your queries in this particular dataset, depending on the features you used. An example I failed on is to use pitch class profiles as feature representation, and test on a small set of Chinese ballad songs, which often have very similar chord progressions and tonality.

Another note is that the current biggest open-sourced CSD dataset generally represents Western music context, and might not be generalizable to other regional music genres and types. It might be an exciting problem to explore if transfer learning (pre-train - fine-tune) helps CSD models adapt from one genre to another. To sum up, there are too many aspects of variations that cover songs could possess, and no single public benchmark dataset could possibly summarize all of them in its entirety.

Metrics Used May Not Reflect Practical Needs

For a very long time, CSD has been formulated as an information retrieval problem - “given a song, can you retrieve the most similar cover tracks?” This is why retrieval based metrics like mean average precision (mAP), mean rank, P@10 etc. are used in academia up until now. However, there rarely is a use case for CSD in such recommendation-like scenarios. More often, the use case looks like “given a track (original / cover), can you tell me which work it belongs to?”, which is more relevant to an identification problem (and much like person re-ID). Hence, metrics like top K accuracy, precision, recall, etc. should be a more suitable and straightforward metric to assess the system. However, most research papers do not report these metrics and hence making it difficult to compare on them.

Computer Vision-Based Models Perform Best?

ByteCover is currently performing best on most of the large-scale benchmark datasets, including SHS-100K and Da-TaCos. The backbone of ByteCover is basically a ResNet-IBN model, which is a common architecture used in face re-identification problems (see this re-ID strong baseline paper). This makes me wonder if CSD problems, or even MIR problems, can be solved in general using computer-vision based methods by merely having music represented in CQT spectrograms, even replicating the trajectory of model improvements proposed in the re-ID domain. If common CV-based models work so well, this also makes me wonder if previous proposed “musically-aware” network architectures are actually learning about music features that we desire. Is domain-specific architecture design less important, as compared to general model training techniques (e.g. annealed learning rate, BNNeck, loss function choices, pooling methods etc.)? This would be a question that I would love to seek answer for.

4 - Conclusion

CSD systems are gaining more and more attention in the music tech field, from startups to huge DSPs, especially due to the increase in amount of published music thanks to digital streaming, which creates a huge demand for efficient rights management, and hence accurate music identification systems. Given the long history of CSD, there might already be answers for solving some of the problems mentioned above, and there will definitely be a strong demand for bridging academia research and industry needs in this field (much like the face recognition domain years ago). It would be no doubt that CSD technology will play a vital role in the music industry, especially on the publishing, licensing, royalties payout and legal aspects in the very near future.

5 - Further References

1 - Yesiler et al. - Version Identification in the 20s - ISMIR2020, ISMIR 2020 Tutorial.

2 - PhD thesis Defence on Cover Song Detection by Guillaume Doras - link